October 28, 2025 • Ocean Facts

Across the world’s oceans, few creatures capture the human imagination quite like the humpback whale. Known for their acrobatic breaches, mesmerizing songs, and migrations that span entire ocean basins, humpback whales are more than icons of marine wildlife. They are vital engineers of ocean health. Each stage of a humpback’s life, from birth in warm tropical waters to feeding in icy, nutrient-rich polar seas, supports the balance of marine ecosystems. These whales are not just gentle giants; they are powerful agents of planetary resilience, playing a key role in nutrient cycling, carbon sequestration, and the upkeep of ocean biodiversity.

Understanding the life cycle and ecological importance of humpback whales reveals how the survival of these whales is directly linked to the health of our oceans and, by extension, our planet.

This deep dive explores their remarkable journey, their unseen contributions beneath the surface, and why protecting humpbacks is essential to safeguarding the future of our oceans.

The Life Cycle of a Humpback: From Birth to Migration

Birth and Early Life

Humpback whales begin their lives in warm, shallow breeding grounds located far from the colder feeding areas where their mothers spend much of the year. These calm tropical waters are free from major predators and provide ideal conditions for newborn calves, which are born without the thick blubber needed to survive in colder regions.

At birth, a humpback calf is typically 10 to 15 feet (3–4.5 meters) long and can weigh up to 1.5 tons. The calf immediately forms a strong bond with its mother, who nurses it with milk that can be up to 50–60% fat. This highly nutritious milk enables the calf to gain as much as 100 pounds (45 kilograms) per day. Throughout these formative weeks, calves stay close to their mothers, learning critical behaviors such as breathing at the surface and developing the strength they will need for their first migration.

During this time, the mother does not feed and relies solely on fat reserves built during the feeding season. The calf’s early survival depends entirely on the mother’s health and the safety of the breeding grounds.

A humpback calf and its mother eye us curiously. © Doug Perrine

Growth and Development

Within just a few months of birth, humpback whale calves are strong enough to begin their first migration alongside their mothers—often traveling thousands of miles to polar feeding grounds. As they develop, calves begin displaying more active behaviors such as breaching, tail slapping, and pectoral fin slapping. These behaviors, while seemingly playful, play an essential role in their development. They help build muscle strength, improve coordination, shed parasites, and aid in communication – skills that will be critical throughout their lives.

Humpback calves are typically weaned between 6 and 12 months of age, at which point they begin feeding independently on krill and small fish in cold, nutrient-rich waters. During their first year, they experience rapid growth, gaining several feet in length and hundreds of pounds in weight. After weaning, young humpbacks spend several years feeding extensively to build energy reserves until they reach sexual maturity, which occurs between 5 and 10 years of age.

Long-Distance Migration Patterns

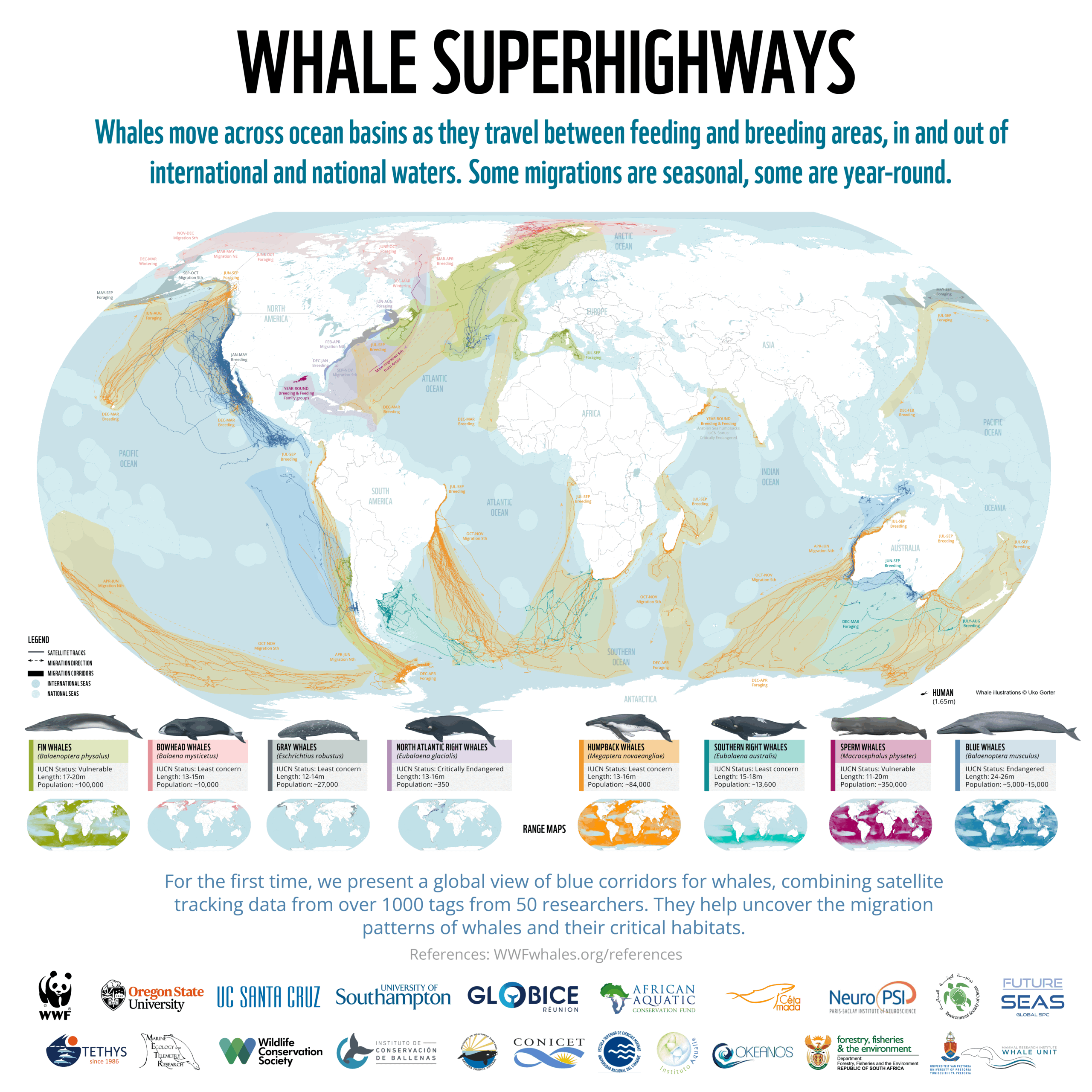

The humpback whale undertakes one of the longest migrations of any mammal on Earth – traveling up to 5,000 miles each way between breeding and feeding grounds. In the Southern Hemisphere, humpbacks travel between Antarctica’s nutrient-rich summer feeding areas and tropical breeding grounds such as Tonga and Fiji. In the Northern Hemisphere, they migrate between Alaska and Hawaii, or between Baja California and the Pacific Northwest. These critical migratory routes, known as “Blue Corridors” or ocean “superhighways,” connect key habitats for feeding, breeding, and birthing for whales and other marine megafauna.

Whale Superhighways: Whales migrate thousands of miles each year along “blue corridors”—vital ocean routes that connect feeding and breeding grounds. Protecting these migratory pathways is essential to the health of whale populations and marine ecosystems worldwide. © WWF World Wildlife Foundation

These migrations serve a dual purpose: reproduction in the tropics and feeding in colder waters where krill and small schooling fish are abundant. Humpbacks may spend four to six months fasting during migration and breeding season, sustained solely by fat reserves. Once they reach polar waters, they initiate intense feeding cycles, consuming up to 3,000 pounds (1,360 kilograms) of food per day.

Their migration does more than support their own survival; it also plays a critical role in distributing nutrients across ocean ecosystems, a process scientists now recognize as essential for marine productivity. Every journey a humpback makes helps sustain life across vast oceanic regions, connecting ecosystems thousands of miles apart.

How Humpback Whales Contribute to Ocean Health

Nutrient Cycling and the Whale Pump

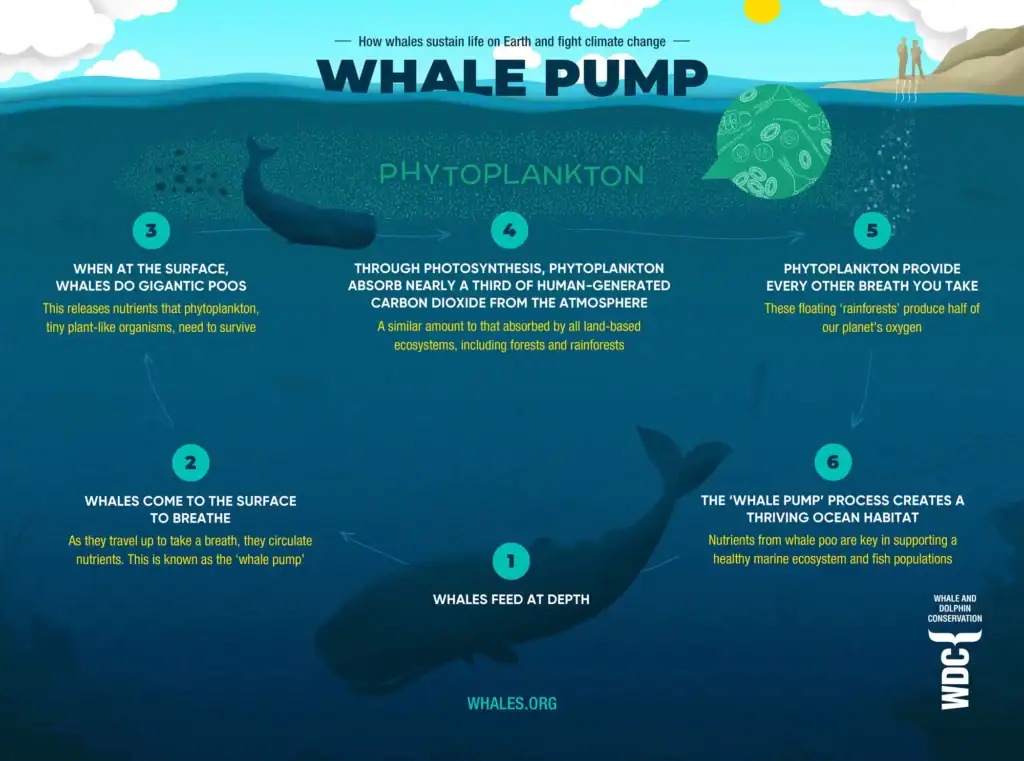

Large baleen whales, including humpbacks, are increasingly recognized by scientists as ecosystem engineers—species that actively shape their environment in ways that enhance biodiversity and productivity. One of the most impactful ways they do this is through nutrient cycling, specifically via a process known as the “whale pump.”

Although humpbacks feed at depth, they return to the surface to breathe and rest, releasing nutrient-rich waste into the sunlit upper layer of the ocean. Their fecal plumes are rich in iron and nitrogen, key nutrients that stimulate the growth of phytoplankton, the microscopic organisms that form the foundation of the marine food web.

The Whale Pump: Whales play a vital role in ocean health by cycling nutrients through the water column. When they feed at depth and release waste near the surface, they fertilize phytoplankton—the base of the marine food web—helping support life across the ocean and capture carbon from the atmosphere. © WDC Whale and Dolphin Conservation

Phytoplankton are responsible for producing more than 50% of the world’s oxygen and play a critical role in absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. By enhancing phytoplankton growth, humpbacks indirectly support global oxygen production, marine biodiversity, and carbon sequestration.

The effect is seen across ocean basins. In nutrient-poor tropical breeding grounds, whales fertilize surface waters that would otherwise be low in productivity. In polar feeding grounds, their presence has been shown to stimulate millions of tons of phytoplankton growth each year. Their movement, through migration, feeding, and even tail slapping, helps mix ocean layers and distribute nutrients across vast distances.

In short, where whales go, life flourishes. Rebuilding whale populations is not only a conservation goal, it is a natural climate solution with global ecological benefits.

The Wonder of Whale Fall: Life After Life

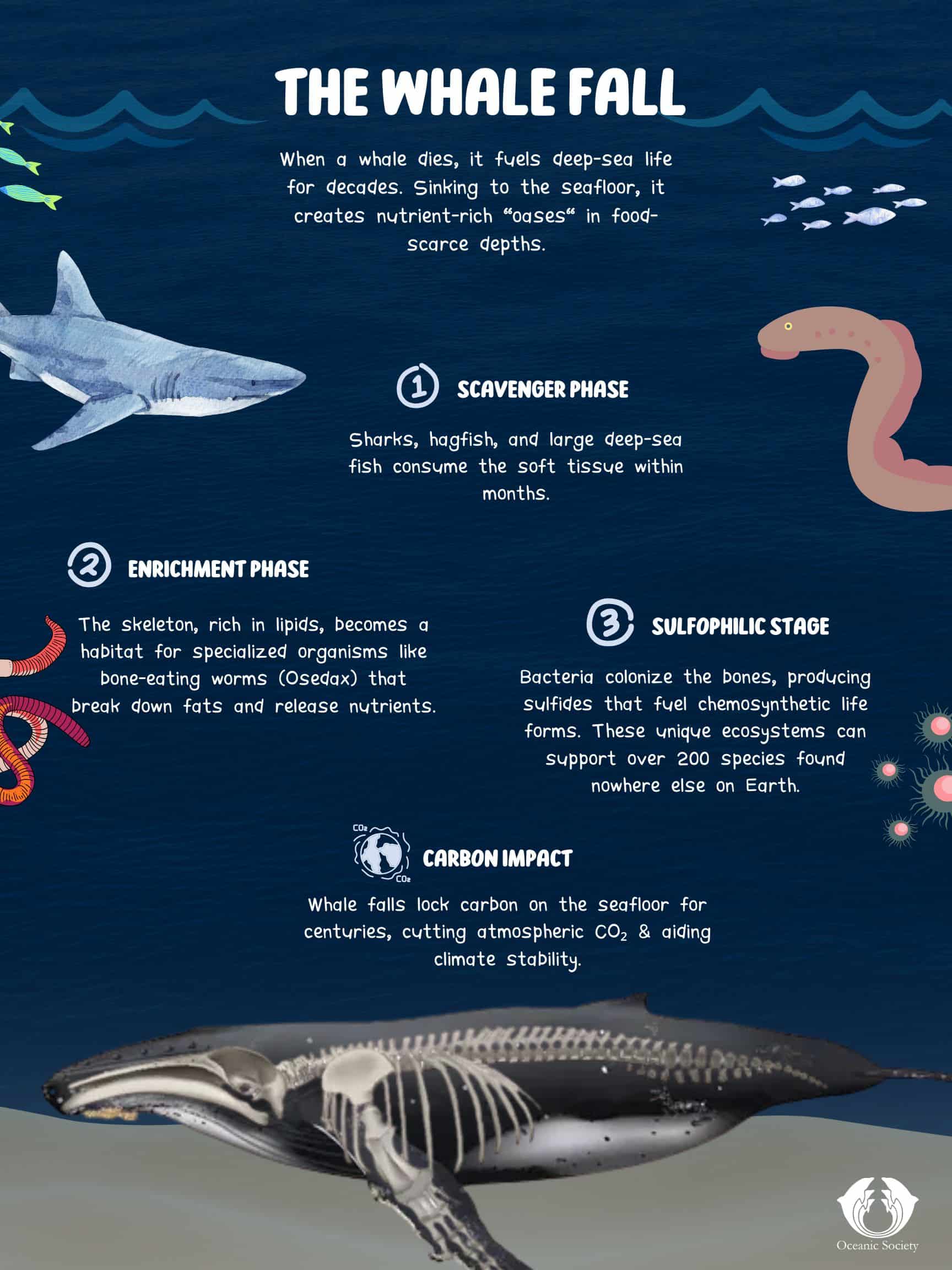

When a whale dies, its ecological contribution does not end. Instead, it enters a new and extraordinary phase known as a “whale fall.” As the body sinks to the deep seafloor, it creates a sudden, concentrated source of nutrients that can sustain entire ecosystems for decades.

In the deep ocean, where food is scarce, whale falls are oases of life. The process unfolds in stages:

- Scavenger Stage: Sharks, hagfish, and large deep-sea fish consume the soft tissue within months.

- Enrichment Stage: The skeleton, rich in lipids, becomes a habitat for specialized organisms like bone-eating worms (Osedax) that break down fats and release nutrients.

- Sulfophilic Stage: Bacteria colonize the bones, producing sulfides that fuel chemosynthetic life forms. These unique ecosystems can support over 200 species found nowhere else on Earth.

Discover the ‘whale fall’ phenomenon: How a humpback whale’s final journey sustains deep-sea ecosystems for decades while sequestering carbon. From scavengers to chemosynthetic wonders, it’s nature’s ultimate legacy. © Oceanic Society

Whale falls are also important to the global carbon cycle. When a whale’s body sinks, much of its stored carbon is transferred to the seafloor, where it can be locked away for centuries. This process helps reduce carbon in the atmosphere and contributes to long-term climate stability.

For humpback whales, whale falls represent the final phase of their ecological legacy. Once contributors to surface productivity through feeding and migration, they continue nourishing the ocean long after their lives have ended. As humpback populations recover globally, the natural return of whale falls will help restore deep-sea ecosystems and enhance long-term carbon storage on the ocean floor.

Humpback Songs: Communication Across Oceans

Humpback whales are renowned for their complex songs – structured vocal displays made up of repeating patterns of moans, clicks, and pulses. These songs typically last 10 to 30 minutes and are often repeated continuously for hours. Only males sing, usually during the breeding season, suggesting a primary role in reproduction.

Each song is composed of units (individual sounds) that form phrases, which are repeated to create themes. These themes are performed in a specific order, similar to verses in a human song. What makes humpback songs extraordinary is that all males within the same population sing nearly the same version at any given time, and these songs evolve slowly over months. Entire populations may collectively adopt a new song within a single season in a phenomenon known as cultural transmission. This behavior is one of the strongest parallels to human language and shared culture in the animal kingdom.

Why Whales Matter – And the Role of Humpbacks in Ocean Recovery

Large whales, including humpbacks, are essential to the health of the ocean. Their migrations, feeding behavior, and even their deaths contribute to nutrient cycling, carbon storage, and the overall productivity of marine ecosystems. Whales help fertilize surface waters, support phytoplankton growth, and transport nutrients across ocean basins. Simply put, when whale populations are healthy, ocean ecosystems function more effectively.

Humpbacks are a powerful symbol of what is possible through conservation. Once driven to near extinction by commercial whaling, many populations are now recovering thanks to international protection. Their rebound is not only a success story for a single species, but a sign that ocean ecosystems can recover when given the opportunity. However, the work is not done. Whales today face threats from entanglement, ship strikes, noise pollution, habitat loss, plastic pollution, and climate-driven changes in prey distribution.

A humpback whale breaches just meters from our boat in Tonga, a highlight of Oceanic Society’s ethical whale-swimming expeditions that prioritize whale safety and conservation. © Chris Biertuempfel

How You Can Be Part of Their Future

Every person has the power to support humpback recovery and ocean health:

- Adopt a whale to contribute directly to research and protection efforts

- Share whale tail photos on platforms like Happywhale to help scientists track migrations

- Name a whale in perpetuity and ensure its story supports conservation for years to come

- Travel responsibly and experience whales in the wild through programs that support local conservation, such as Oceanic Society’s expeditions in Tonga

- Reduce plastic use and support ocean-friendly legislation in your community

Protecting whales is an investment in the health of the ocean and the stability of our climate. Their recovery is a reminder that conservation works, and our continued commitment will determine the future of our blue planet.